When to Stand and When to Run (2021)

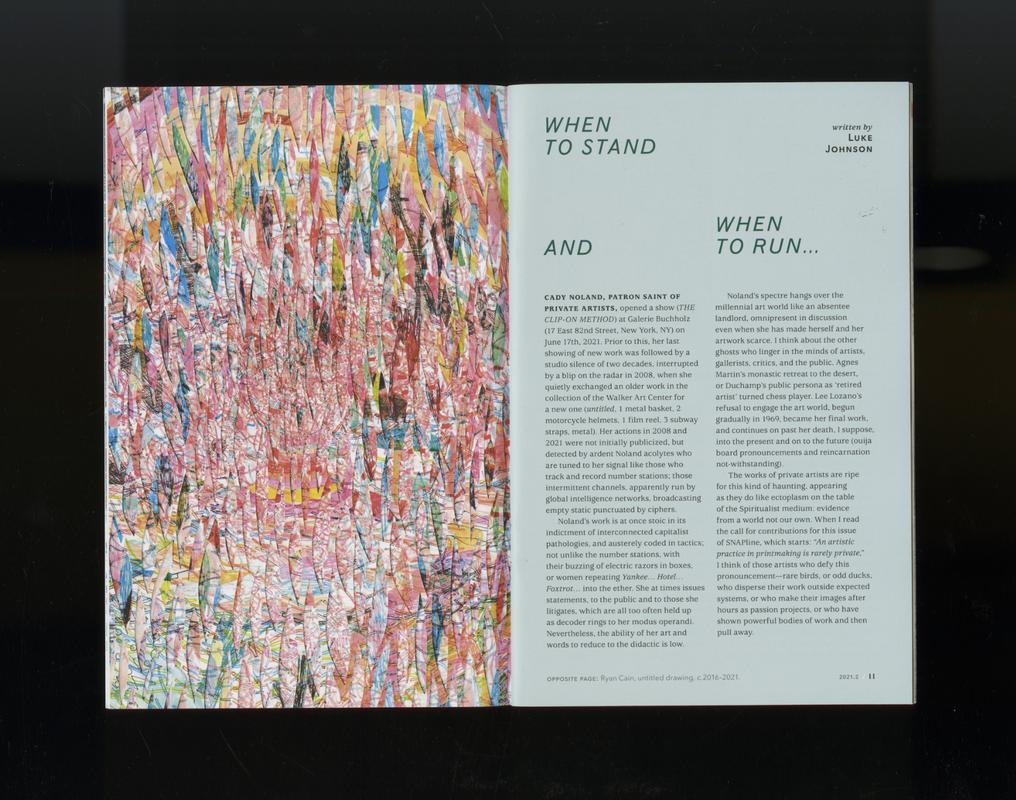

essay on artworks by Ryan Cain, C. Couldwell, and Rebecca Aronyk, included in SNAPline, issue 2021.2

essay on artworks by Ryan Cain, C. Couldwell, and Rebecca Aronyk, included in SNAPline, issue 2021.2

Excerpt:

Cady Noland, patron saint of private artists, opened a show (THE CLIP-ON METHOD) at Galerie Buchholz (17 East 82nd Street, New York, NY) on June 17th, 2021. Prior to this, her last showing of new work was followed by a studio silence of two decades, interrupted by a blip on the radar in 2008, when she quietly exchanged an older work in the collection of the Walker Art Center for a new one (untitled, 1 metal basket, 2 motorcycle helmets, 1 film reel, 3 subway straps, metal). Her actions in 2008 and 2021 were not initially publicized, but detected by ardent Noland acolytes who are tuned to her signal like those who track and record number stations; those intermittent channels, apparently run by global intelligence networks, broadcasting empty static punctuated by ciphers.

Noland’s work is at once stoic in its indictment of interconnected capitalist pathologies, and austerely coded in tactics; not unlike the number stations, with their buzzing of electric razors in boxes, or women repeating Yankee… Hotel… Foxtrot… into the ether. She at times issues statements, to the public and to those she litigates, which are all too often held up as decoder rings to her modus operandi. Nevertheless, the ability of her art and words to reduce to the didactic is low.

Noland’s spectre hangs over the millennial art world like an absentee landlord, omnipresent in discussion even when she has made herself and her artwork scarce. I think about the other ghosts who linger in the minds of artists, gallerists, critics, and the public. Agnes Martin’s monastic retreat to the desert, or Duchamp’s public persona as ‘retired artist’ turned chess player. Lee Lozano’s refusal to engage the art world, begun gradually in 1969, became her final work, and continues on past her death, I suppose, into the present and on to the future (ouija board pronouncements and reincarnation not-withstanding).

The works of private artists are ripe for this kind of haunting, appearing as they do like ectoplasm on the table of the Spiritualist medium: evidence from a world not our own. When I read the call for contributions for this issue of SNAPline, which starts: “An artistic practice in printmaking is rarely private,” I think of those artists who defy this pronouncement—rare birds, or odd ducks, who disperse their work outside expected systems, or who make their images after hours as passion projects, or who have shown powerful bodies of work and then pull away.

...

The full article can be read on the SNAPline website.

Cady Noland, patron saint of private artists, opened a show (THE CLIP-ON METHOD) at Galerie Buchholz (17 East 82nd Street, New York, NY) on June 17th, 2021. Prior to this, her last showing of new work was followed by a studio silence of two decades, interrupted by a blip on the radar in 2008, when she quietly exchanged an older work in the collection of the Walker Art Center for a new one (untitled, 1 metal basket, 2 motorcycle helmets, 1 film reel, 3 subway straps, metal). Her actions in 2008 and 2021 were not initially publicized, but detected by ardent Noland acolytes who are tuned to her signal like those who track and record number stations; those intermittent channels, apparently run by global intelligence networks, broadcasting empty static punctuated by ciphers.

Noland’s work is at once stoic in its indictment of interconnected capitalist pathologies, and austerely coded in tactics; not unlike the number stations, with their buzzing of electric razors in boxes, or women repeating Yankee… Hotel… Foxtrot… into the ether. She at times issues statements, to the public and to those she litigates, which are all too often held up as decoder rings to her modus operandi. Nevertheless, the ability of her art and words to reduce to the didactic is low.

Noland’s spectre hangs over the millennial art world like an absentee landlord, omnipresent in discussion even when she has made herself and her artwork scarce. I think about the other ghosts who linger in the minds of artists, gallerists, critics, and the public. Agnes Martin’s monastic retreat to the desert, or Duchamp’s public persona as ‘retired artist’ turned chess player. Lee Lozano’s refusal to engage the art world, begun gradually in 1969, became her final work, and continues on past her death, I suppose, into the present and on to the future (ouija board pronouncements and reincarnation not-withstanding).

The works of private artists are ripe for this kind of haunting, appearing as they do like ectoplasm on the table of the Spiritualist medium: evidence from a world not our own. When I read the call for contributions for this issue of SNAPline, which starts: “An artistic practice in printmaking is rarely private,” I think of those artists who defy this pronouncement—rare birds, or odd ducks, who disperse their work outside expected systems, or who make their images after hours as passion projects, or who have shown powerful bodies of work and then pull away.

...

The full article can be read on the SNAPline website.